Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

12-06-2016, 10:38 PM

(This post was last modified: 12-06-2016, 11:09 PM by Alanus.)

Obviously, nobody is making money on these two books, and I respect Bunker for her tenacity and expertise in helping put together volumes on an obscure subject. I notice that official museum books often end up as PDFs, but I really enjoy the "actual" photos in correct color. Better to spend $20 on something like this than $85 for Craig Benjamin's book without even a map, and NO photos... not even on the cover!!!!

Another good and cheap "picture" book is, The Golden Deer of Eurasia, published by the Met and the Russians. It starts off with the finds of Filippovka (Early Sarmatian), then shows Scythian art-- all those Manly Men doing their Mano-a'-Mano things, and not one artifact showing a woman (in an obviously male-dominated society). The volume concludes with Pazyryk art, some of the best photos of Pazyryk animal-style yet published.

Starting with Bunker and China's Northern Zone, these books cover societies that seem to have a hand in the Alan genesis, with the exception of the western Scythians who appear to be cultural "throw-backs."

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

(12-06-2016, 07:57 PM)Dan DSilva Wrote: (12-05-2016, 12:09 AM)Alanus Wrote: Her longest dagger (#9) is almost a forerunner of an akinakes. It measures 17 inches, has a semi-mushroom pommel, one side of which is engraved with a "portrait"-- a round-faced man with a brachycephalic skull, also commonly called "Andronovo," "Ferghana-Pamir," or more accurately "Siberian."

Hello, hope you don't mind me focusing on such a small part of this very interesting post. I'd recently read about the Krotov-culture and Karakol daggers, which seem to me to be the forerunners of the akinakes. But they lack guards, while these more easterly ones have a rudimentary one; perhaps the historical akinakes is a fusion of the styles?

And as with the Karakol daggers, the appearance of this one from Baifu puts me in mind of nothing so much as a long spearhead with the socket turned into a hand grip.

Dan, the Karakol daggers appear to have the same or close origin with the Baifu daggers, their predecessors being the Seima-Turbino phenomenon. I don't know when the dagger first showed up, but the idea (as you say) may have come from early bronze spear heads. Also, I can't pinpoint the emergence of the akinakes but one may have been within the artifacts found at Arzhan 1. Surprisingly, photos or even drawings of Arzhan 1 artifacts are almost nil.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 61

Threads: 4

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

3

One of the museum books is actually on Amazon (or the museum store) for 75 USD, so not that cheap. (I think the older edition might be cheaper though) Archive.org is mostly legit, so they might've let it slip into free access. (a great site for out of print, or out of copyright books, btw)

I edited my post on the previous site with links to ebay, for a bunch of these types of knives/daggers.

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

I PMed you on those links. A couple of them look like my knife, but not my dagger. I bought them as a set, which is historically correct. Some of these "gray bronze" fakes go for $200. My guess is they're brass.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 15,116

Threads: 415

Joined: Mar 2002

Reputation:

76

(12-07-2016, 12:46 AM)Alanus Wrote: I PMed you on those links. A couple of them look like my knife, but not my dagger. I bought them as a set, which is historically correct. Some of these "gray bronze" fakes go for $200. My guess is they're brass.

Sorry guys, the forum rules are clear on this - NO links to sites where unprovenanced antique items are sold. Fakes or no fakes.

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

Sorry about that, Robert. (Evidently the links have been removed, either by Mod or Jan.)

Actually, we got off-topic. Baifu burials M2 and M3 are important; they tell a story and have wider implications. Baifu appears to be a State of Yan command post on the northern frontier. The enemy was the Shanrong, which certainly had its share of early riding gear. I'm working on it for my next post.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

12-12-2016, 03:02 AM

(This post was last modified: 12-12-2016, 10:27 PM by Alanus.)

Baifu M1, 2, and 3: Dying at the Front Line.

We return to Baifu and all of its implications. The two intact graves exhibit "wealth" in a sense that those buried there were from the upper strata of a tripart society-- a combination of Zhou, Shang, and an unknown "ghost" culture from the Far North. In Baifu M2 and 3, the central clusters around the bodies contain northern bronze artifacts, similar to the ones found in Karasuk and Arzhan graves. Around the periphery of both burials, we find large bronze containers of both Shang and Zhou style, only reserved for the highest "upper crust." The woman commander in M2 was given the most attention by those who interred her, but the log chamber was roughly cut with no mortise work. The officer in M3 was lying face down, as if hastily dropped to his grave (or in an extended prostrate position, not fully described by the author [Csorba, Sept. 1, 1996, Antiquity]). However, indications point to rushed interment.

If we look at an area map, we find Liulihe (the Yan capital) about 90 km south. The frontier stations-- Baifu, Xiaohenan, and Chaodaogou-- are located equidistant from each other in a straight line that runs west-southwest to east-northeast. They form a 200 kilometer "front line" and face the Yan Mountains. The enemy would be the "Shanrong," pastorals attacking from the lower regions of Yanshan. This accounts for the hurried burials. The three officers in Baifu 1, 2, & 3, were commanding a defensive war under the direction of the Marquis of Yan (who was probably quite safe back at Liulihe).

Here are some artifacts found in Shanrong graves. And here too, we see Northern-styled horse bits, artwork, and bronze riding gear similar to those discovered at Arzhan 1.

We have no facts to decipher when this woman commander's culture entered northeastern Shang China. They were quite Sinicized at the time the Zhou amassed 500 chariots against the last Shang king (whose wife was recorded as a "fox demon"). There's no news like old news; and back in 1980 Karl Jettmar phrased it this way, " Tribes participating in the battles that led to the shift of power from Shang to Chou [Zhou] certainly reveal cultural traits of East European origin, either because they were immigrants themselves or because they had accepted innovations of immigrants... [The three Baifu] burials in wooden chambers belong to a transition period from Shang to Chou... The victorious Chou installed a new dynasty there [in Yan] whose symbol could be a prototype of the 'tamgus' used during later periods by the peoples of the steppes." (Jettmar, 1980, p.149)

We have several indications that the northern tribes were well inside Shang China for at least four generations, going back to the tomb of Fu Hao, and the 50 Alpine (Adronovo) skulls found in Anyang's sacrificial pits. Anthropologist Yan Sun has referred to the woman in M2 as a "local elite," indicating her tribe was within the Yan polity, in touch with the central Zhou court, and favored by it. She was an accepted leader of an Indo-Iranian pastoral community at the frontier of Zhou society.

I'll relate more info in a future post, especially the prominent Zhou family of Peng Bo, which falls into haplogroup Q1a1a. (Same haplogroup mentioned in an earlier post on Bronze age DNA within Altai graves) In closing, I should mention that the woman commander in M2 was buried with Shang oracle bones, cowrie shells, and jade waist pendants. She was "Shangized" and less related to Zhou culture. The waist pit beneath her body contained a single dog (Fu Hao's tomb contained six canines), another Shang burial custom. More to come, hopefully.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

12-16-2016, 05:52 PM

(This post was last modified: 01-22-2017, 04:50 PM by Alanus.)

Correction on the Status of Baifu M3 (not M2... but the male in M3)

In the above post, I described the presumably rushed burial of the military officer in Baifu M3. Most unusual was the position of the body-- lying face down in an extended prone position. Such a position could indicate the body was simply tossed into the burial pit, or might signify "disrespect." In the case of Baifu M3, the "prostrate" position of the interred was a cultural marker. Although unorthodox, other prone-position burials have been found within the Zhou polity.

The military individual in Baifu 3 appears to be a descendant of the Tevsh culture (1,400-1,200BC), a tribe discovered in southern Mongolia who buried their dead in a prone position. At some point, the Tevsh tribe (tentatively identified to Siberian haplogroup Q1a1) continued south and entered Shang China. They became members of the Zhou polity, particularly, it would appear, in military positions. I'm in the process of documenting the "Andronovo Trail" from Minusinsk Siberia to Zhou China and will post the results in the near future. Thank you for following this thread.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

12-18-2016, 07:28 PM

(This post was last modified: 01-22-2017, 03:40 PM by Alanus.)

From Minusinsk to Northeastern China: the Q Migration, Part 1

If Andronovo tribes migrated immense distances from the Karasuk culture to northern China, they would have followed two routes. The western migration seems to have taken the river Ob south, swung east below the Altai through Dzungaria, reaching the Tian Mountains, settling the Tarim Basin, and finally reaching Gansu. This route is popular with current archaeologists/anthropologists; it creates "news," and splashes photos of dried mummies with colorful clothes in pop venues such as Facebook and the History Channel. It's good for archaeology, creates books, and spurs young hopefuls to write a master's dissertation and climb the academic ladder.

That's fine, but there was a second migrational route from Siberia to China-- a Southeastern one down through Mongolia-- but nobody writes about it. I'm not sure why historians never mention it. If you look at the map (above), you can see the two routes. The eastern migration is actually easier; you don't have to go around the northern Altai. It's not thrilling, has no wonderful mummies to photograph, and would result in the driest info-blogs on the internet. The Southeastern Migration has its plus side: it's shorter, runs though prime Mongolian pasturage, and actually has an archaeological, pictographic, and genetic documentation between "Point A & B" (something not found for the western route).

Let's start at Minusinsk. The Karasuk culture is dated from 1500 to 800 BC, and has the cultural artifacts we find in the early centuries of China's Northern Zone-- bronze animal-headed knives, bronze jewelry, and indications of the chariot. In the photo above, we see examples of two Karasuk male burials, both individuals in a supine position and interred with a chariot rein-holder across their waist-- the strange "bow-shaped object" found in Fu Hao's tomb and also with the warrior-woman in Baifu M2. The rein-holder alone creates a tangible connection between Minusinsk and China. (Also notice the individual at the left carries his bronze knife on a waist-belt, the right-hand individual carries his knife on the right thigh like a akinakes. Both knives have a sheep-head pommel.)

Next, we can turn to genetics. Not much work has been done in the Minusinsk basin. An old study gave three out of four positive Y-DNA results on Karasuk males: Q1a1b1, R1a1a1b, and R1a1a1b2a. These came from a single site and do not reflect the general Bronze age population, nor do we see any information on female mtDNA-- the highest frequencies actually being Haplogroup A (highest in eastern Siberia, and even higher in Amerindian populations). For our purposes, we will follow Q (male) and A (female) in its journey south through the Mongolian steppes. Also, a recent study on hair and eye color was done on a small number of Bronze age individuals from Minusinsk's Krasnoyarsk graves, the results in the above photo. Note the genetic origins of the individuals are both "European" and "Asian" (Siberian).

This is our starting point. From the above map, we head southeast between the Eastern and Western Sayan mountain ranges. In the smaller map (upper right-hand corner), we enter Mongolia to the east of the Altai and migrate south. For our purposes, let's define a time-period, perhaps 1400BC... 100 years after the Andronovo culture entered Minusink. We have everything we need, our chariot, a handy bronze knife, and a motive to find new grazing lands... to actually form the oldest archaeologically-defined equestrian culture.

(more to come)

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

12-23-2016, 03:51 PM

(This post was last modified: 01-22-2017, 03:40 PM by Alanus.)

From Minusinsk to Northeastern China: the Q Migration, Part 2

Actually, it was more like an "expansion" rather than a migration. Why? Around 1,400 to 1,200 BC, climate change resulted in more humid and wetter conditions throughout the Siberian and Mongolian steppes. Pastoralist's animal herds increased in size, and they were healthier. And likewise, the people themselves ate better and actually became more robust as their own population increased. This was a major catalyst to expand into new grazing areas. See: theguardian.com/science/blog/2016/dec/07/archaeology-sheds-light-on-Mongolia

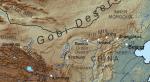

Here is a map of the first leg of the expansion. In the far upper right corner, we find "Minusinsk" (in tiny little itty-bitty print). From there, we head upstream along the Yenisey River, heading east between the Western and Eastern Sayan Mountains. For most of this trek, we're actually in Tuva and bypass the actual location where Ahrzan 1 would be built 300 years later. We reach the Yenisey headwaters in northern Mongolia, a large valley just west of "Hovsgol Nuur" (Khuvsgul Lake). From there, we drive our herds of cattle, sheep, and horses straight south to the spot marked as "Hangayn Nuruu." (After right-clicking on the map, you can click it again to enlarge and scroll down.)

A photo of the Tuvan steppe as it looks today. In 1,300 BC, this area was incredibly verdant and able to feed larger populations of grazing animals than it can today (an area now endangered by over-grazing by sheep).

"Hangayn" is actually Khangai, a large mountain range, pastoral complex, directly in the center of Mongolia. About the size of the Gorni Altai region, Khangai is loaded with everything we might expect from a circa 1,300 BC pastoral population. The above panoramic photo shows the extensive Bronze Age burial and khirgisuur complex located in Khangai.

The Bronze Age khirgisuurs in Khangai were built round and square, and the round ones are similar to those found in the Gobi Altai (our final destination in southern Mongolia). Khirigsuurs usually contain a single central grave of a "hero" or "chieftain." To the east of a khirgisuur, we find small burials containing horse skulls, vertebrae, and hooves. The horse skulls (just like the human skeletons) usually face to the east... toward the sun, the symbol of renewal. Often, a deer stone is also located to the east.

The Khangai complex is loaded with thousands of Bronze Age petroglyphs. Everything from deer, mountain sheep, hunters with bows, and chariots, are found within the artwork. For us, chariots are a key item.

Here is a simplified map of the route. The upper-left valley is Minusinsk. Going east, we see a small valley (Yenisey headwaters) just west of Khuvsgul Lake. Below this area, we see the large Khangai cultural complex. And directly below Khangai, we reach the Gobi Altai. At this point, we are only 550 km (342 miles) from Hetao, the "hump" of the Yellow River. Let's take a break and water the livestock before we continue.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

01-01-2017, 05:42 PM

(This post was last modified: 01-22-2017, 03:48 PM by Alanus.)

From Minusinsk to Northeastern China: the Q Migration, Part 3

Now that the livestock has been watered, we continue our journey. We head directly south from the Khangai Mountains and reach the Gobi Altai. While a portion of the Gobi is desert, a vast steppe area runs parallel to it along the northern and eastern side.

The Gobi is one of the last places to find wild steppe horses. Here, we see two mares and a foal as they would have appeared before domestication. More than 200 bird species, 600 varieties of plants, and the endangered Gobi bear, constitute a plethora of wildlife.

Areas of the Gobi also contain the largest expanse of Bronze age petroglyphs. At Bayangiin Nuyuu, Del Mountain, Bayan Uul, and Tevsh Uul, in the heart of the Gobi, more than 3,000 petroglyphs have been found, some of them pecked on rocks 30 feet above the ground. The petroglyphs at Tevsh Uul contain the largest number of wheeled vehicles yet found in eastern Asia.

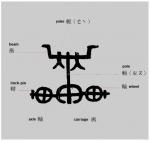

Interestingly, at least for us, depictions of chariots are shown in two different dimensions, looking down at it while the wheels are viewed from the side. First illustration (above), chariot from Tevsh Uul. Second illustration, symbol for "chariot" in Shang Dynasty writing.

The pastoralist presence at Tevsh Uul is substantial, not just from petroglyphs, but from the remarkable "waisted graves" which predate other (and simpler) styles of slab burial. Like barrows in the Altai, almost all of these graves have been looted, leaving us with few clues and disturbed (and stripped) skeletons. Here are descriptions from three archaeological reports dating from 1996 to 2016:

"The most striking, well documented Bronze age finds were recovered from the excavation of three kurgans at Mount Tevsh uul on the eastern slopes of the Gobi Altai... The funeral rites were identical in all three cases: burial in a narrow pit, face down, with the head towards the east. Over 560 paste beads, 126 carnelian beads and 24 turquoise beads were found in two graves, as well as 200 hemispherical bronze plates of different sizes [typical Scytho-Siberian clothing plaques], stone grindstones and a painted fragment of pottery."

"In addition to beads, the third grave contained two unique, solid gold hairpins lying on either side of the skull. The ends of the hairpins are decorated with heads of mountain rams, finely executed in Karasuk style. Small cylinders set with turquoise are cast along the outer edge of the hairpins. They are decorated with horizontal notches, also typical of Karasuk style." (p.1049, History of Humanity, Vol. II, Edited by A.H. Dani and J.P. Mohen, 1996, UNESCO, Routledge)

Here is a drawing of the Tevsh Uul hairpins, the ram-heads shown upside down. Now we hear from A.A. Kovalov and D. Erdenebaatar, 2009, " The assemblage of burial goods included golden hair ornaments topped with images of sheep heads... According to their design, they are similar to items of the north Chinese nomadic culture of Shang-Yin period. Knives, ornaments, daggers and scoops designed in the same style are of well established dates... thus the Tevsh culture may be dated to 1,400-1,200 BC. According to published materials, a barrow that had been excavated by A.W. Pond in 1928 near Lake Tairum in the eastern part of Inner Mongolia belongs to the same culture. A burial of a human being placed in prone (face-down) position with the head directed to the east was discovered there; the clothes were decorated by more than 5,000 beads."

Recently (June, 2016), the Tevsh site was revisited by Kazuo Miyamoto, who did a superb analysis to two more individuals from the figured pit graves. Tevesh M1 was a woman buried supine, while Tevsh M3 was a male, buried face down. They were both C14 dated to 1,392-1,264 BC, with a mean average of 1,328 BC. Both were compared with average individuals from Bronze age graves in Inner Mongolia, Henan, Shanxi, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Siberia. They were larger and more robust, the male at 171.5 cm. " The Tevsh M1 female had a healed fracture in left middle-leveled rib. The curve of the rib body was unnaturally bent in the medial direction. The Tevsh M3 male had three healed fractures in nasal bones, left femur, and the lower-leveled thoracic vertebrae... the two lower vertebrae, which deformed into a wedge shape, were fused together."

Miyamoto adds this, " According to physical anthropological research, the people of the Tevsh site are taller in height compared with other prehistoric peoples of East Asia. They sustained far more injuries than hunter-gatherers or farmers as a result of accidents related to riding horses... They had a more nomadic lifestyle than other peoples."

The Tevsh M1 woman and M3 man are the oldest extant examples of horse riding. We have speculations by David Anthony, Elena Kuzmina, and a dozen other archaeologists, but these two individuals are physical proof. I'll let you sift out the further implications found at Tevsh Uul-- the petroglyphs of chariots, the custom of decorating clothing with hundreds of beads and plaques, the hair-pins fashioned in Karasuk style, and the odd practice of prone (prostrate) inhumation.

Oh! I forgot to mention Dr. Miyamoto conducted DNA tests. The Tevsh M3 male test failed, but the Tevsh M1 female was from Mt- Haplogroup A, the most common haplogroup of Siberian women. And last-- if you go out riding on this New Year, don't fall off your horse and break your nose. Thank you for following this thread.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

01-22-2017, 10:29 PM

(This post was last modified: 01-23-2017, 04:12 AM by Alanus.)

From Minusinsk to Northeastern China: the Q Migration, Part 4-- the "Sino-Siberians"

In the 3 above posts, we have followed the Siberians from Minusinsk, across Tuva, down through Mongolia, where we find them at Tevsh Uul, right on the eastern corner of the Gobi Altai. We also know (from Part 3 above) that the same culture-- males buried in a prone, face-down, positions-- have been found in Inner Mongolia.

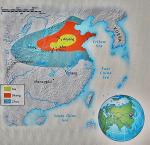

The trek continues, punctuated by petroglyphs of chariots scratched on two mountain ranges-- at the western tip of the Yinshan and along the eastern side of the Helanshan. The migratory trajectory from Tevsh Uul into China was directly south. The above map shows the Gobi mountains, so picture a movement straight down to the Yellow River.

Once below Hetao, "the hump in the Yellow River," this culture moved southeastward occupying what is now eastern Shaanxi, and in particular, southwestern Shanxi, right where the Yellow River turns from its southern course and flows directly to the east. The map shows the Shang Dynasty in red and the subsequent Zhou Dynasty in blue. The western part of the Shang area was settled by a Siberian " Lijiaya culture... thought to have been an area of horse breeding and possibly a transit point for chariots coming from the steppe into the Shang core." (Gina L. Barnes, Archaeology of East Asia, Oxbow, 2015)

West of this area, on the periphery of the Shang sphere, we see the duchy of Hao, which I believe was a settlement founded by King Wu Ding and governed by his third wife Fu Hao. In other words, Hao was not her family or tribal name. She appears to come from the Xia Zhi.

The Xia Zhi appear to be contemporaneous to the Lijiaya culture and occupying the same ground. Initially, King Wu Ding conducted a short war against them, a ten month campaign. This brief encounter seems to have ended in a prosperous treaty for both sides. The Xia Zhi received recognition as a Shang prefecture, attested by the high number of ornate Shang vessels in their burials. In turn, Wu Ding gained chariot technology and an extremely bad-ass third wife from the "Zhi family." The rest, of course, is history. The Lijiaya prospered, and graves contained much more than the usual "northern bronzes and Karasuk-style knives," including gold chariot rein holders (those "bow-shaped objects") and gold, wrap-around, Andronovo arm bands. There's nothing quite like gold... except maybe jade.

We can fast-forward to the second bad-ass woman, the one in Baifu M2, buried supine with her skull-bashing mace, and her male "companion," the guy lying face down in a prostrate position. We have shades of Tevsh Uul in first-generation Zhou China. The woman commander and her accomplice become the first known "Sino-Siberians." Possibly they were related to Lijiaya and the Xia Zhi. The Lijiaya culture was a substantial one; at least 10 different sites have been found. Also, they liked building things with well-placed rocks, just as the Tevsh Uul folks created ornate waisted slab burials. Wickedly odd, or not, the Zhou polity overlays the Lijiaya culture and the gold-wearing Xia Zhi people. The first Zhou capital, just west of Lijiaya, was at the duchy of Hao, another incidence of odd happenstance.

Let's fast-forward again, this time to the decade just prior to 900 BC. We'll take a little tour of the Peng Clan cemetay at Hengbei. We can visit more dead people, not just mostly dead but Totally Dead. Again, oddly enough, a convenient Yellow Dot on the above map locates the Hengbei cemetery right in the middle of the former Lijiaya/Xia Zhi area... or, in fact, did the Xia Zhi actually became an important Zhou entity called Peng?

The Peng cemetery dates to second generation Zhou, the final resting place of Peng Bo ("Duke of Peng") and his wife Bi Ji. The above photo shows Peng Bo's grave as excavated, the Duke found in " a prostrate position." Bi Ji, on the other hand, was " in an extended supine position with her hands placed across her belly." It's deja-vu all over again!

We are extremely fortune to have a detailed Y-Haplogroup list of the Peng cemetery's occupants. Grave M1 contains Bi Ji, the Duke's wife, descended from a well-heeled Chinese paternity, Haplogroup O. We turn to Peng Bo, the "aristocrat" in M3. His paternal lineage is Haplogroup N, about as Siberian as you can get without reaching the North Pole.

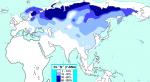

I'm not joking. Here is the map for Y-Haplogroup N. These Siberians hadn't heard about Global Warming yet, and you know they wore heavy fur coats.

The Peng cemetery list records more than 50% of its individuals as Y-Haplogroup Q, most common in Siberians. (see Map) If we look back to the grave list, twelve of the twenty-two occupants were buried prostrate. However, we do not know the sex of each individual, and certainly-- like Bi Ji-- a good percentage of the deceased must have been women.

This takes us back to Tevsh Uul in the Gobi Altai, with the males buried prostrate while a woman was interred supine. It takes us to Baifu, the woman warrior lying supine while her male companion was face-down. This is culturally echoed at Hengbei. There's a exceedingly distinct probability that those buried prostrate in the Peng Clan cemetery were men, while those buried supine were their Chinese wives (many of those listed as Y-Haplogroup O from their father's lineage). Among steppe tribes, it was common (and preferred) to marry outside of the clan. But any way we evaluate it, Duke Peng of the Zhou was a Sino-Siberian... as were the majority buried at Hengbei. Archaeologists and Anthropologists have claimed the Zhou " were aided" by steppe tribes in defeating the Shang. I would go a step further-- a significant portion of the Zhou polity included Siberian steppe people.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 61

Threads: 4

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

3

I think you did mention these "bow shaped objects" found in the Northern zone and also in Fu Hao's tomb.

I'm fairly convinced they're actually rein holders for chariot driving. I've seen them reconstructed like that a few times by reenactors and in paintings, worn at the belt. I wondered why there.

![[Image: bow-shaped-object-m54.jpg]](https://kaogu.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/bow-shaped-object-m54.jpg)

Before going to bed I've just been reading on deer stones and what a surprise, there they are! Worn on the belt, along with other tools:

![[Image: deer-stones.jpg]](http://www.everythingselectric.com/wp-content/uploads/deer-stones.jpg)

(not sure which specific one this is, the paper attributes it as "Saian Altai deer stones per Volkov's typology")

The MET describes them thus:

Quote:"Often described as "bow-shaped," and thought to have been associated with chariotry, this fitting has a hollow central section with curved arms ending in rattles. Fittings of this type first appear in China with the introduction of wheeled vehicles in the thirteenth century B.C., and are not found there after the tenth century B.C. Comparable pieces, which have arched arms but lack rattles, are also found at early Karasuk-period sites (?12th–?10th century B.C.) in southern Siberia.

In Chinese burials, they are generally found in pairs near the chariot box in front of the charioteer. In southern Siberia, on the other hand, the fittings cover the deceased's pelvis. Their function remains unclear: they have been identified as bow-guards, crossbow fittings, and banner ornaments. It has also been suggested that they were either rein-holders, worn by a charioteer at his waist to free his hands, or rein-guards attached in some fashion to the front of the chariot."

![[Image: hb_26.203.2.jpg]](http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/images/hb/hb_26.203.2.jpg)

I'd have to go look, but I remember Mike Loades doing experiments with driving a chariot using reins attached to his waist. (and him commenting it was surprisingly viable, just by twisting the hips)

Oh and here's a whole paper on these (haven't read it yet though):

http://www.kaogu.cn/uploads/soft/Chinese...issues.pdf

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

Thanks for the informative post, Jan.

In some of the above posts, I referred to these rein holders as such, although often called "bow-shaped objects." If we look at your post, we discover rein holders hung from belts on "Saian Altai deer stones." These deer stones, along with the chariot petroglyps, present a marked route from the Minusinsk Basin, upriver along the Yennisey, through the Sayan Mountains (aka "Saian"), and straight southeast through Mongolia to the eastern edge of the Gobi Altai, and finally directly south to Hetao (bend in the Yellow River).

After I finished the first 3 posts on the "Q Migration," I was hoping I wasn't embarrassing myself. Just before the 4th post, I received William Honeychurch's, Inner Asia and the Spatial Politics of Empire, (Springer, 2015) What a relief! Honeychurch concurs with Wu (2013), noting, " In fact, the main evidence that Wu provides for a northwestern introduction (via Mongolia) rather than a western one (via Xinjiang-Gansu) is that the particular toolset associated with Shang period chariot burials, including steppe style bronze knives, whetstones, and curious bow-shaped objects, are known only from two other contemporary contexts: Karasuk period burials in Minusinsk and from carvings on the Mongolian deer stones." (Honeychurch, p. 192)

Jan, you were right on target. And speaking of archery, I've spent 15 years at drawing composite steppe bows. The idea that these "bow-shaped" objects could be related to archery is something invented by the unknowledgeable. I read Mingyu Teng's PDF on the subject (as you linked us to). While he has the right idea, even the wide-based rein holders were not necessarily always strapped to the front of a chariot. All rein holders were designed to be attached to the human body, just above the waist at the lower abdomen, and configured in a concave fashion expressly for this purpose. Some wide-based versions were attached to the carriage-front simply because they worked better than narrow-based ones. Nice to see at least four of them were found in Fu Hao's tomb.

I may have posted this before, but here is one of the rein holders from Fu Hao's tomb. It's 15.7 inches long, certainly not something you would attach to a nice light composite bow for no particular purpose. Note her four bronze mirrors, all of them of Andronovo origin... as is the Karasuk knife.

What is important, at least to me, is the slight cultural difference between this northern group (predominantly Y-Haplogroup Q and linked to the Zhou) and the western group still stalled back in Western Xinjiang and mostly Y-Haplogroup R1a1. Also, according to Honeychurch, we need to reevaluate the Baifu burials into a new context of horse procurement. I'll address the increased need for horses in another post. Again, thanks.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

Posts: 2,011

Threads: 41

Joined: Jun 2008

Reputation:

57

02-19-2017, 07:00 PM

(This post was last modified: 04-01-2017, 11:57 PM by Alanus.)

A Final Analysis: the Siberian Intrusion in Shang and Zhou China

This is an after-thought but an important one, and does not discuss the increased use of the chariot in Chinese culture. It simply addresses the continuity of the Siberian prostrate position as a cultural marker within the larger context of the Shang and Zhou polities. This oldest archaeological and genetic Siberian intrusion appears to be linked to the later, and documented, arrival of the Yuezhi, a confederation with the same Siberian cultural marker (upturned moustache, no beard), and therefore relates to the later split of the Aorsi/Alans (upturned moustache, no beard) from the Kushan Empire (upturned moustache, no beard).

We find a similar continuity within the burials of a certain intrusive sector in this early period. The Tevsh Uull graves, Pond's Inner Mongolian burial, the Baifu graves, and the Duke of Peng cemetery, all carry cultural markers in a unique burial style. The prostrate position is not seen in a Chinese context, nor is it found westward in the Tarim Basin or greater Xinjiang Province.

Starting in 1,300 BC at Tevsh Uul, the burial style continues into Shang China and is seen within the chariot burials at the capital city of Yinxu (Anyang). A study of this intermediate site connects the Gobi Altai graves to the Peng Clan tombs. It's the missing "link." Turning to 1,250-1,200 BC Anyang, there are at least a dozen published PDFs available, all written by good academics. All of these studies detail the positions of the chariots within each grave. Yet-- amazingly enough-- not one study, not one professor, has detailed the physical position of the driver (or drivers) within the burials. Unfortunate that the vehicle becomes more important than the human.

In the photo above, we see a typical chariot burial [Yinxu grave M52]. (Please click on the photo, then click on it again for enlargement to see important details) The two horses are attached to the chariot. The sacrificed driver at the upper right has his hands tied behind his back. He lies in a prostrate position. (This is noticeable by his head facing downward, the visible presence of his scapulae, and his heels being upward.) A second driver lies to the rear of the chariot box, and he is also lying prostrate. What a remarkable coincidence! Two charioteers sacrificed by the Shag are lying in a specific burial position Not Used in the Chinese culture.

How can we explain this? Is this some kind of deja vu all over again?-- a strange coincidental echo of Tevsh Uul, and a odd precursor of the Peng burials? The only logical explanation is this: at Yinxu, the residence of King Wu Ding, a group of Siberians were incorporated into the Shang army and oversaw the chariot burials. They specifically positioned a prisoner in that prisoner's cultural burial position. Any other explanation will not fit the fact that a totally unique burial practice, never used by the Shang, could be found in chariot burials.

I can only find three detailed photos of this burial practice at Anyang. Here is a second black and white example of the prostrate position. This photo also shows 2 "bow-shaped objects" (rein holders) in the grave. A third photo, in color and taken by archaeologist Marsha Levine, shows another prisoner of war in a similar chariot burial. A drawing of a chariot burial in Gideon Shalach-Lavi's The Archaeology of Early China shows a normal supine position (Cambridge, 2015, p. 210). Such a small sample isn't ideal, but it reveals a cultural trait totally overlooked by previous scholars writing about chariot burials. The chariot tells us something. The charioteer tells us Everything.

Alan J. Campbell

member of Legio III Cyrenaica and the Uncouth Barbarians

Author of:

The Demon's Door Bolt (2011)

Forging the Blade (2012)

"It's good to be king. Even when you're dead!"

Old Yuezhi/Pazyrk proverb

|

![[Image: bow-shaped-object-m54.jpg]](https://kaogu.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/bow-shaped-object-m54.jpg)

![[Image: deer-stones.jpg]](http://www.everythingselectric.com/wp-content/uploads/deer-stones.jpg)

![[Image: hb_26.203.2.jpg]](http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/images/hb/hb_26.203.2.jpg)